At the TOTAL RECALL Symposium session on September 8, 2013, the topic of the day will be the origins and history of various archiving technologies. Frank Hartmann, media philosopher and professor of visual communications, will speak about Paul Otlet, the inventor of an archiving system with many similarities to the ones we’re familiar with today. As a sort of prelude, the Ars Electronica Blog is publishing an extensive interview—the first in a series of presentations of this year’s symposium speakers.

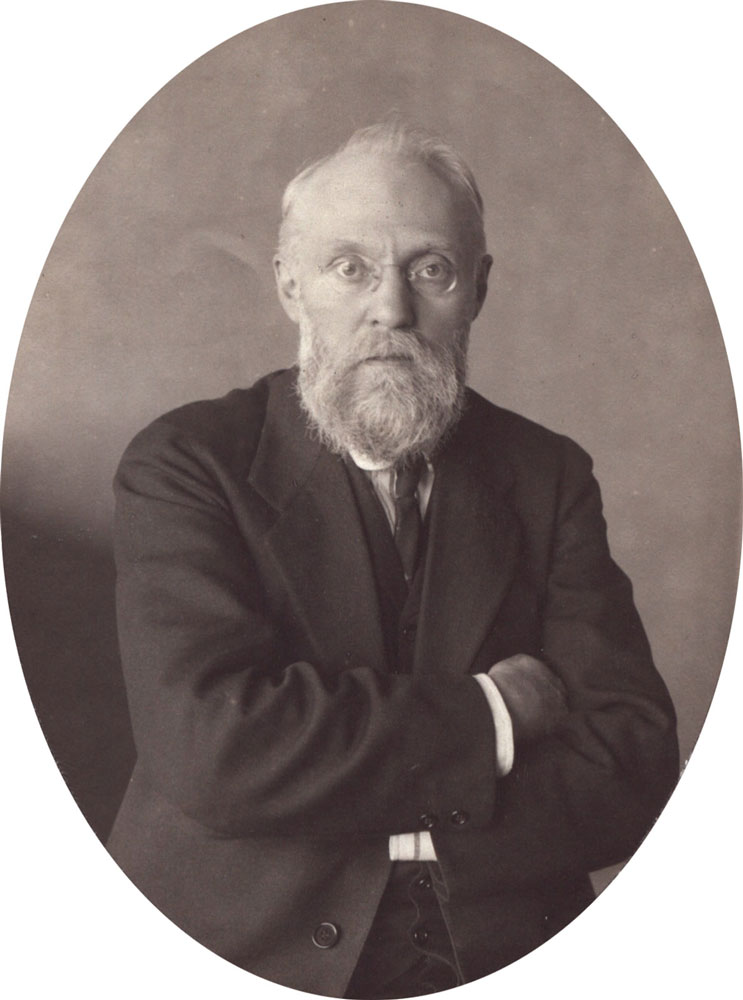

Prof. Dr. Frank Hartmann

From your perspective as a media philosopher, what role does memory play for us as human beings and for us as a society?

Remembrance should not be considered individually since it’s a collective phenomenon, like the way it occurs in, for example, myths, fairy tales and legends. We “moderns” often think only of the individual with a humanistic education and his capacities, whereby the corresponding cultural techniques of storage and transmission target cultural memory that, in the modern concept of education, is totally underestimated or simply assumed. We are also completely fixated on current communication, whereas the basis of culture is the capacity to transmit from one generation to the next.

It’s very simple. A human lifetime just isn’t long enough to acquire comprehensive knowledge about, say, medicine or architecture. The human being builds upon the experiences of others, on trials and errors of previous generations. There’s no other way, since intelligence is a collective achievement. That’s why we have language, writing, images, archives, institutions, etc. Ideas can make an impact only if they’re propagated. Thus, memory is the depth dimension of any culture, and here we also see the fundamental significance of myths, religions and laws.

As Paul Valéry once maintained: “Man’s greatest triumph over things is having understood how to transfer the effects and the fruits of labor from yesterday to tomorrow. Humankind has become great only because of the mass of that which endures.” This thought seems so simple, but it implies that techniques of remembrance in our culture play a far greater role than the much-praised brainstorms and so-called inventions.

What will the heritage of the current generation, of our epoch, look like? What will we leave behind, and in what form?

That’s a tough question. I mean, who are “we”? And leave behind to whom? Historically, memories of those considered insignificant are systematically expunged, although those who wield power aren’t necessarily the ones who have the best ideas. Furthermore, what’s considered important changes over time because it has to be recontextualized. So then, who are the ones to whom our contribution will someday be important or not? For a long time, all that counted as the voice from the past was that which the chronicler felt was worth writing down, and that was undoubtedly the perspective of power. Then, everyday life gradually shifted into the center of attention. For instance, someone discovers, stuffed between two timbers, a pair of underwear from the Middle Ages that can impart a tremendous amount of information to us about life back then. Underwear—the chronicler seated at his scriptorium surely never considered that. After all, what’s important is what’s written down!

Every account handed down from the past privileges a certain medium. We usually don’t have the possibility of evading this filter; it’s possible to draw only indirect conclusions—such as the very things that were never written down. But it doesn’t become directly accessible to us. One concept of modern archiving is to document a topic as broadly as possible and independently of current interest so that, even if interests change, the corresponding data will be available. So, what’s important to us could be regarded much differently in the future, since we don’t know the premises according to which this will be judged someday. Attitudes and preferences change, and of course the storage media do too.

The past century was the first that was equipped with photographic recollection. What came about was a completely new pictorial memory. What will now be left behind is something I dare not consider because the developments and preferences are unclear. Albrecht Dürer knew that his paintings would still be around in 500 years, and that won’t change over the next 500 either. Who today produces something like that? And is this even desirable? What from today’s world will still be recalled (and quite a lot will be) depends on the transmissions that we opt for technically and culturally.

It also has to be mentioned that our storage technologies are quite fragile. Accordingly, for the long-term archiving of cultural treasures, the medium of choice isn’t electromagnetism; rather, it’s still microfilm sealed in drums welded shut and kept in central storage bunkers (e.g. the Barbarastollen underground archive in Breisgau, Germany). At least this is how the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property is being implemented.

Media shape our perception; they can form and influence opinions. What means do media producers have at their disposal now and in the foreseeable future to influence the public? Are there new insights, new tricks?

I recommend a useful exercise to all those who would like to leave behind something enduring: Humbly going on an extended excursion to humankind’s Cultural Heritage Sites.

You teach in the area of visual communication. What role does this play in producing memories, also in comparison to other channels of communication?

As far back as Aristotle, thinkers have privileged the sense of sight among human sensory capabilities. I’m rather skeptical about this. Attributing superiority to a particular mode of sensory perception always depends on interests with which they’re prescribed. But our culture is currently undergoing something that I’m not going to call a deluge of images but rather an enormous proliferation of visual input. It is outrageous what is presumed to be suitable for viewing. If a culture of eroticism consists of covering up the object of desire and suggestively, promisingly intimating it, then our culture of totally explicit exposure can rightfully be described as a shamelessly pornographic one.

But let’s face it—we also need the visual level for functional reasons now that our technology has withdrawn from sensory perception. But it nevertheless takes place behind the graphic surfaces. Images, surfaces, interfaces everywhere, and with them the appurtenant design questions, the consideration of which goes far beyond what, say, experts in visual culture treat as a theoretical problem. What I mean is that this isn’t a matter of images, but rather of the significant shift of communications into the visual realm.

First of all, this has to do with the expansion of surfaces. Paper production and graphic reproduction broadly “unfold” so to speak cultural goings-on, and nowadays the omnipresent computer screens compound this. And whether we want it or not now—in order for us to orient ourselves, we have to immerse ourselves in these unbounded surfaces. Otherwise, all of this technical “know-how” (ability in the sense of a potential) is of no use at all. I differentiate between a “weak” skill that makes it possible to get by amidst prevailing facts & circumstances, and a “strong” skill that brings forth new possibilities. For instance, one can teach students the outcomes of certain colors or typefaces, but this is banal. One can also teach them to avoid conformist thinking, or support them as they learn it themselves.

For example, do we cite the plaques affixed to the Pioneer space probe to discuss how graphic or typographic comprehensibility can be improved? Or do we talk about whether the idea of communicating with extraterrestrials in this way even makes sense. This applies in a figurative sense to future generations too. Who are we to constantly believe that we have to “communicate” something?

The fact that, in media development since the advent of photography, visual perception has so dramatically appreciated in value can also be regarded functionally. It’s the visual level that permits quick orientation. Nobody needs, say, traffic signs as long as traffic volume remains low. There are these rather over-the-top fantasies about an “ideal language,” but visual signs can’t be beat when it comes to intercultural comprehensibility. Nevertheless, we have no business even getting involved in an attempt to create a strictly defined basis of communication for the process of historical transmission.

We’d be well advised to leave the definition of what will be important someday to the intelligence of future generations. We’re unable to anticipate that now.

Icons are central to our collective memory. How does one create icons? What factors do the perception of them depend upon? How does one keep from drowning in the flood of information?

I view all this talk about a flood of information rather skeptically. Basically, the amount of available information always exceeds the human sensory apparatus’ ability to process it. Over the course of evolution, a selection schema has emerged. The physiological limitations are now being rescinded by technical means, and, for instance, we’re seeing things with a microscope or a telescope that are completely invisible to the naked eye. We thereby expand our view of the world, though how one evaluates this is another matter. Consider this example—the media have been annoying us ever more frequently of late with so-called “images” from deep space, whereby these are sights that a human being in a space ship out there could never see. These are pictures that NASA has construed from data as a depiction of how this part of the universe could imaginably look. The Santa Claus Syndrome is what I call this: Santa Claus really does exist when everybody really and truly believes in him. Now, this brings us to icons, which are essentially visual condensations.

History is full of attempts to create and propagate such condensations, and a faint imitation of this is provided by the manufacturers of brand-name merchandise. But intellectuals aren’t immune to this either—beyond all mental appropriations, figures such as Franz Kafka and Walter Benjamin function as icons of an intellectual attitude. This means a particular photo that has attained the status of a visual stereotype (like the picture of Einstein sticking out his tongue).

We’re living in obscene times. You go to the supermarket and see a guy wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with Che Guevara’s face, and the guy has absolutely no idea who that was. It simply looks cool, like Benjamin in his nickel-frame spectacles. I don’t dare draw a conclusion from this. Whether something works or not just depends upon ones interpretation. Whoever attempts to leave behind a certain “image” might be interpreted totally differently than he’d prefer.

Paul Otlet

At the symposium, you’re going to talk about Paul Otlet. What can people today learn from him?

Paul Otlet’s life is testimony to a historical epoch that can still impress us with the radicalism of the questions it asked. He wasn’t a great theoretician, but he invested great hope in ordering knowledge. I was surprised that, about 100 years ago, people were already confronting issues that we now associate with the internet. His vision and foresight were fascinating. He saw that this was not only a matter of the knowledge stored in books, but rather of new forms of production and distribution of knowledge—for example, via the new telegraph networks.

But we also learn from the case of Otlet that knowledge is no substitute for politics. People have repeatedly fallen for the illusion that there will be no more wars in a knowledge-based age. It turned out differently, as we all know. It’s also interesting that the great intellectuals obviously missed the boat on this subject of new knowledge formats. They lived totally immersed in their world of books. Otlet, on the other hand, kept his gaze fixed on a world in which the privilege of education would be available to all. Here, we notice a close proximity to other social reformers like H.G. Wells, Wilhelm Ostwald and Otto Neurath. These people called for realizing the potential of Modernism in radical terms, whereas many intellectuals engaged only in rear-guard actions.

One can also learn a bit of humility. After all, what is the power of all this technology without the corresponding ideas? And Otlet, who had potent ideas, approached the men of technology; he demanded solutions from the engineers. This ultimately impresses me the most—that someone didn’t just wait for the possibilities that technology offers but made an effort to activate them.

Frank Hartmann will speak at the 3rd Panel of the TOTAL RECALL – The Evolution of Memory Symposium on September 8, 2013 at the Brucknerhaus in Linz, Austria. Check out the full program at ars.electronica.art/totalrecall.